The world’s oceans turned a page in history yesterday. After years of painstaking negotiations and false starts, the High Seas Treaty was finally ratified, crossing the threshold of 60 nations and ensuring its entry into force early next year. For the first time, the two-thirds of the ocean that lies beyond any single nation’s control will fall under a shared framework designed to protect biodiversity, regulate human activity, and safeguard the planet’s last global commons.

The announcement reverberated far beyond diplomatic circles. For environmentalists, scientists, and the small island nations that had long pressed for action, it was the culmination of decades of work. And for a weary multilateral system, often dismissed as incapable of consensus in a fractured world, it stood as proof that collaboration across borders remains possible.

A Long Road to Agreement

Calls to govern the high seas began more than 20 years ago, when scientists warned that fragmented treaties and voluntary codes were leaving marine life dangerously exposed. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which set basic rules for navigation and resource use, never fully addressed biodiversity in international waters. That gap persisted as industrial fishing fleets expanded their reach, corporations eyed deep-sea mining, and researchers mapped fragile ecosystems never before seen.

Momentum toward a comprehensive agreement built slowly. In 2004, the UN established a working group to study the issue. By 2017, formal negotiations were authorized, and a grueling series of sessions followed, with some stretching through the night as diplomats haggled over wording. In March 2023, negotiators struck a deal on a text that balanced scientific urgency with political compromise. The treaty opened for signatures later that year, but ratification required a critical mass of countries willing to bind themselves under international law. That moment has now arrived.

Champions and Skeptics

Small island states were among the earliest and most persistent advocates. For them, the treaty is not an abstraction: the health of the ocean determines food security, culture, and survival in the face of rising seas. Their diplomats pressed hard for provisions on equity and technology-sharing, ensuring that poorer nations could benefit from advances in marine science and participate in enforcement.

They were joined by environmental groups and scientific coalitions, which supplied the data and moral pressure that made inaction untenable. These advocates mapped biodiversity hotspots and highlighted the dangers of unregulated exploitation, keeping pressure on negotiators to deliver more than symbolic promises.

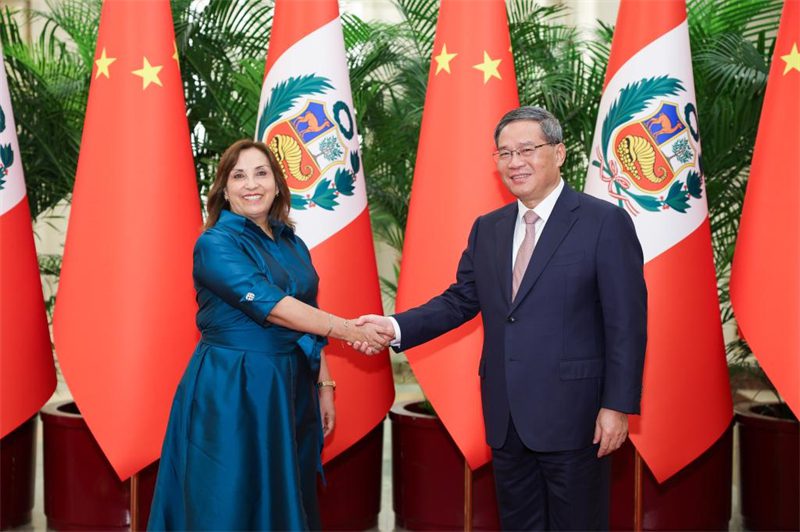

Major powers were slower to move. Some governments feared constraints on lucrative fishing or potential deep-sea mining. Others worried about the complexities of monitoring activity in international waters. The breakthrough came when a critical group of ratifications was secured in recent months, led by European nations and supported by countries across Latin America, Africa, and the Pacific.

What the Treaty Promises

When the treaty enters into force, nations will for the first time have a legal mechanism to establish marine protected areas on the high seas. These reserves are expected to serve as refuges for migratory species, coral systems, and ecosystems still being discovered. Planned industrial activities, whether fishing, shipping, or exploration, will be subject to environmental reviews. The treaty also introduces a framework for sharing the benefits of marine genetic resources, a growing field with enormous commercial potential, and obliges wealthy states to assist less developed ones with training, data, and technology.

The treaty is not without limitations. Some of the largest maritime powers have yet to ratify, leaving questions about enforcement. The capacity to police remote expanses of ocean remains thin, and funding mechanisms are still being debated. Yet the legal structure is now in place, transforming what was once a patchwork of voluntary codes into binding international law.

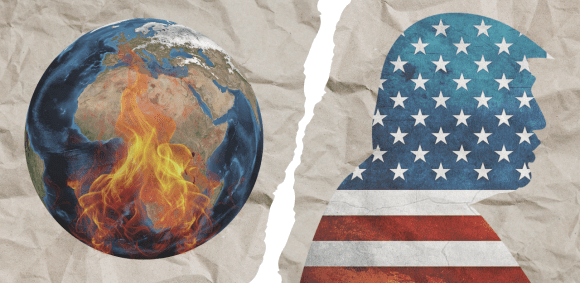

A Signal of What Is Still Possible

The ratification of the High Seas Treaty comes at a moment of profound uncertainty for global cooperation. With conflicts raging, trust in international institutions waning, and climate negotiations often gridlocked, many have come to see multilateralism as paralyzed. The treaty offers a rare counterexample: a case where diplomacy, science, and persistence yielded a tangible result.

It is more than a legal instrument; it is a message. The idea of the global commons, fragile and shared, has not been abandoned. Nations can still come together to defend it. As world leaders descend on New York next week for the United Nations General Assembly, the treaty’s arrival will stand as a hopeful reminder. Even in a fractured age, there remain moments when countries can look past their divisions and act for the common good.

Related Content: Global Push Builds for High-Seas Biodiversity Treaty

Follow SDG News on LinkedIn

Follow SDG News on LinkedIn