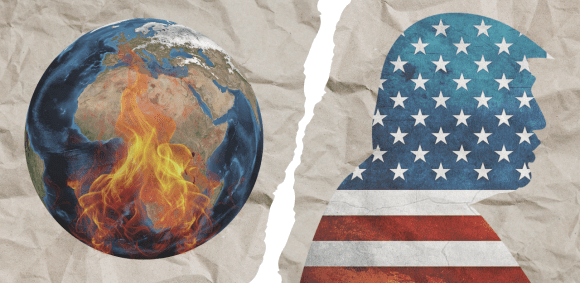

At a moment when scientific warnings about the state of the planet are growing more urgent, the United States has moved to block a core component of a major United Nations Global Environmental Outlook report, aligning itself with Saudi Arabia, Russia and Iran to prevent the release of policy guidance calling for a transition away from fossil fuels, expanded clean energy adoption and reduced plastic use.

The decision marked a historic break in multilateral environmental governance. For the first time since the UN Environment Programme began publishing its flagship Global Environment Outlook reports in 1997, governments failed to approve a “summary for policymakers,” the section designed to translate scientific findings into practical guidance for national leaders.

The blocked section was part of the Global Environment Outlook 7, a 1,210 page assessment compiled over three years by more than 300 experts. The report was formally released this week at the UN Environment Assembly in Nairobi. While the full scientific document was published, the absence of a policy summary significantly weakens its ability to influence government action.

Participants in the negotiations say the Trump administration played a decisive role. During final discussions in October, U.S. officials objected to language addressing climate change, clean energy transitions, biodiversity protection and plastic pollution. Rather than renegotiating the language, negotiators ultimately dropped the summary altogether following objections from the United States and several oil and gas producing nations.

Observers described the intervention as both unusual and disruptive. The United States did not send a delegation to the Nairobi meeting where the report was finalized, yet still intervened remotely to block the language. According to participants, a U.S. State Department official joined negotiations by video conference late in the process to voice opposition to the summary’s conclusions.

“Nonattendance does not mean a lack of influence,” said one of the coordinating authors involved in the negotiations. “It means exertion of influence in a certain manner.”

The move reflects a broader reversal in U.S. environmental policy under President Trump’s second administration. Shortly after returning to office, the United States withdrew from the Paris Agreement, abandoning the global framework to limit greenhouse gas emissions. The administration also declined to attend the COP30 climate summit in Brazil and was accused by multiple governments of using pressure tactics to block a proposed global pollution levy on the shipping industry.

In contrast, the previous administration had treated climate action as a diplomatic priority, frequently clashing with fossil fuel producing states over emissions reductions and clean energy targets.

The stakes surrounding the Global Environment Outlook were particularly high. The report synthesizes existing science on climate change, air and water pollution, land degradation, biodiversity loss and the accelerating crisis of plastic waste. Its findings underscore that environmental decline is no longer a future risk but a present economic and social threat.

The report also emphasizes opportunity. According to its authors, transitioning to clean energy systems and reducing environmental harm could generate global economic benefits of up to $20 trillion annually by 2070, through improved health outcomes, ecosystem services and sustainable growth.

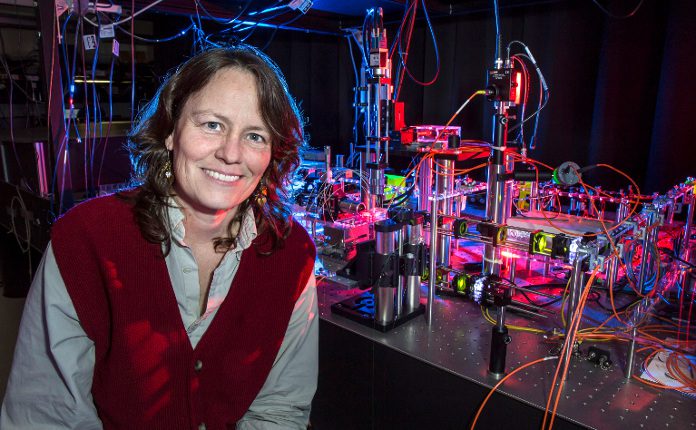

“Fossil fuels must be out,” said Edgar E. Gutiérrez Espeleta, a co chair of the report and former environment minister of Costa Rica, ahead of its release. He called for rapid expansion of renewable energy and increased investment in scientific innovation to replace polluting materials currently embedded in global supply chains.

The decision to block the policy summary has raised concerns well beyond this single report. For decades, the United States has acted as a stabilizing force in multilateral negotiations, helping broker compromises even when it disagreed with outcomes. By opting out of negotiations and then vetoing final language, critics argue the administration is weakening the credibility of international environmental processes themselves.

Analysts warn the implications could be lasting. If scientific assessments cannot be translated into agreed policy guidance, future global agreements on climate, biodiversity and pollution may become harder to achieve. In a world facing converging environmental crises, the breakdown of consensus around shared facts and collective action may prove as damaging as the crises themselves.

As governments confront tightening budgets, rising geopolitical tensions and accelerating ecological decline, the failure to endorse even a plain language summary of the science signals a troubling shift. The science remains clear. What is increasingly uncertain is whether global institutions can still muster the political will to act on it.

RELATED STORIES:

- Unpacking the SFDR: How Asset Managers Are Navigating Sustainability Challenges

- Guest Post: Corporate Renewable Energy Strategies – A Key Building Block for Global Decarbonization & Energy Equity

- Brazil Prosecutors Move to Block $180M Amazon Carbon Credit Deal Ahead of COP30

- Global Africa Business Initiative Pushes for Bold Overhaul of Africa’s Economic Story

- COP30 Outcomes Set New Finance Commitments but Leave Fossil Fuel Phase-Out Unresolved

Follow SDG News on LinkedIn

Follow SDG News on LinkedIn